Astronomers Find Evidence of Cosmic Climate Change

(Originally published by University of Cambridge)

November 2, 2010

A team of astronomers has found evidence that the Universe may have gone through a warming trend early in its history. They measured the temperature of the gas that lies in between galaxies, and found a clear indication that it had increased steadily over the period from when the Universe was one tenth to one quarter of its current age. This cosmic climate change is most likely caused by the huge amount of energy output by young, active galaxies during this epoch.

"Early in the history of the Universe, the vast majority of matter was not in stars or galaxies," University of Cambridge astronomer George Becker explains. "Instead, it was spread out in a very thin gas that filled up all of space." The team, led by Becker, was able to measure the temperature of this gas using the light from distant objects called quasars. "The gas casts a series of shadows on these extremely bright objects," Becker continues, "and by analyzing how those shadows block the background light from the quasars, we can infer many of the properties of the absorbing gas, such as where it is, what it's made of, and what its temperature is."

The quasar light the astronomers were studying was more than ten billion years old by the time it reached Earth, and had travelled through vast tracts of the Universe. Each intergalactic gas cloud the light passed through during this journey left an imprint, and the accumulated effect can be used as a fossil record of temperature in the early Universe. "Just as Earth's climate can be studied from ice cores and tree rings," says Becker, "the quasar light contains a record the climate history of the Universe.

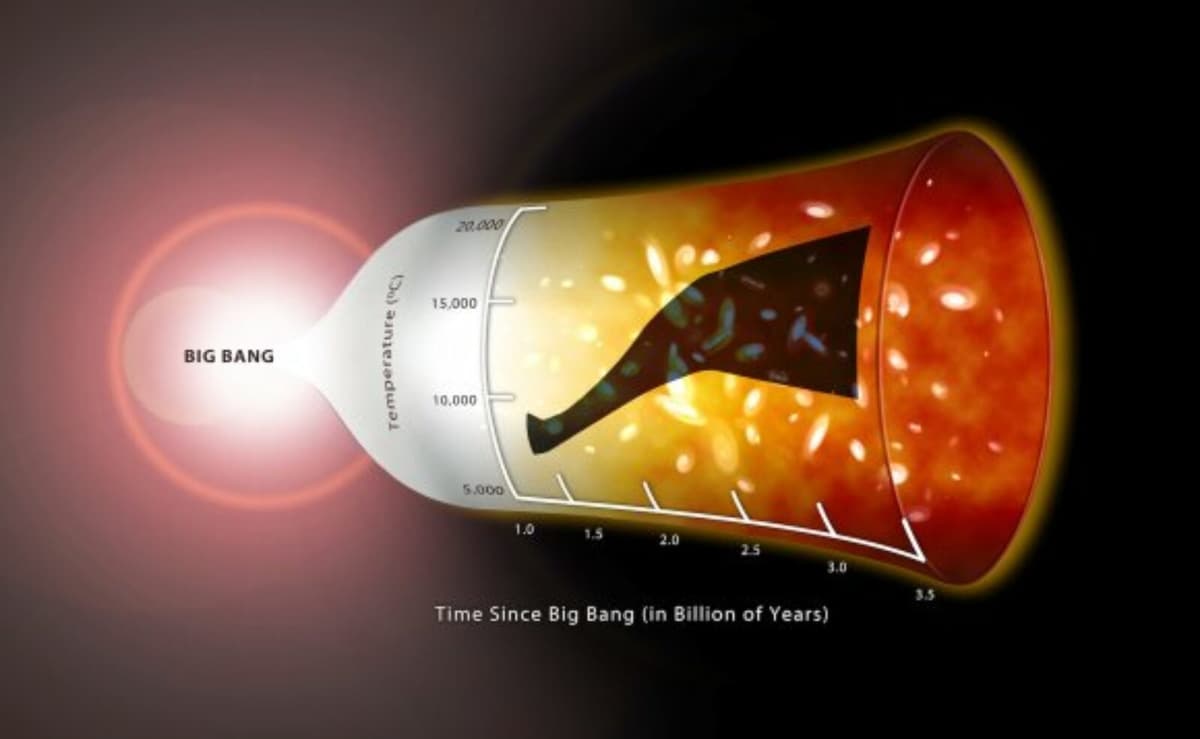

"Of course, the temperatures we measured are a bit different than what you find on Earth," commented Becker. "One billion years after the Big Bang, the gas we measured was a 'cool' 8,000 degrees Celcius.

By three and a half billion years the temperature had climbed to at least 12,000 degrees Celcius." The warming trend is believed to run counter to normal cosmic climate patterns. Normally the Universe is expected to cool down over time. As the Universe expands, the gas should get colder, much like gas escaping from an aerosol can. To create the observed rise in temperature, something substantial must have been heating the gas.

"The likely culprits in this intergalactic warming are the quasars themselves", explains fellow team member Martin Haehnelt, who is also at Cambridge University's newly-established Kavli Institute for Cosmology. "Over the period of cosmic history studied by the team, quasars were becoming much more common. These objects, which are thought to be giant black holes swallowing up material in the centres of galaxies, emit huge amounts of energetic ultraviolet light. These UV rays would have interacted with the intergalactic gas, creating the rise in temperature we observed."

One of the lightest and most abundant elements in these intergalactic clouds, Helium, plays a vital role in the heating process. Ultraviolet light will strip the electrons from a Helium atom, freeing the electrons to collide with other atoms and heat up the gas. Once the supply of fresh Helium was exhausted, the Universe will have started to cool down again. Astronomers believe this probably occurred after the Universe was one quarter of its present age.

The team's discovery was made possible by data taken with the 10-meter Keck telescopes in Hawaii. It was also aided by advanced simulations run on a supercomputer at the University of Cambridge. Along with Becker and Haehnelt, the team included James Bolton at the University of Melbourne, and Wallace Sargent at the California Institute of Technology. Their results are due to be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.