Biochemist Peter Walter Receives 2018 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences

(Originally published by the University of California, San Francisco)

December 4, 2017

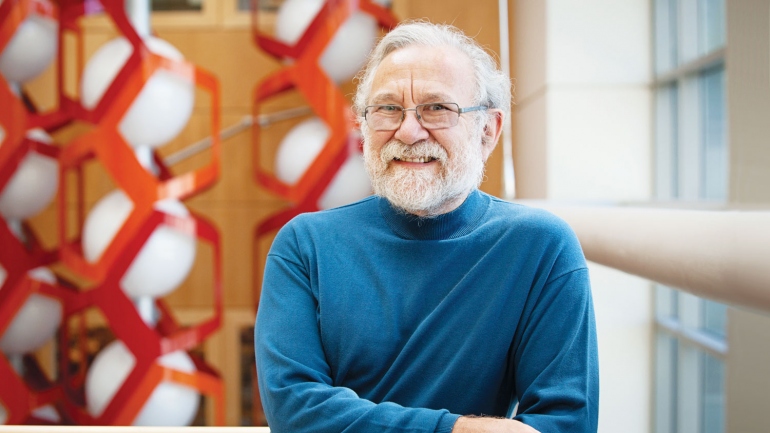

Peter Walter, PhD, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at UC San Francisco, has been named winner of a 2018 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences, for his research on a biological mechanism that normally protects cells, but can cause disease if not functioning properly.

The Breakthrough Prizes, now in their sixth year, were founded by Sergey Brin; Yuri and Julia Milner; Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan; and Anne Wojcicki. The Prizes are “dedicated to advancing breakthrough research, celebrating scientists and generating excitement about the pursuit of science as a career.” They are given each year in Life Sciences, Fundamental Physics, and Mathematics. As many as five prizes are given in each field, and each prize carries a cash award of $3 million.

Walter, 62, was recognized for “elucidating the unfolded protein response, a cellular quality-control system that detects disease-causing unfolded proteins and directs cells to take corrective measures,” according to the award citation.

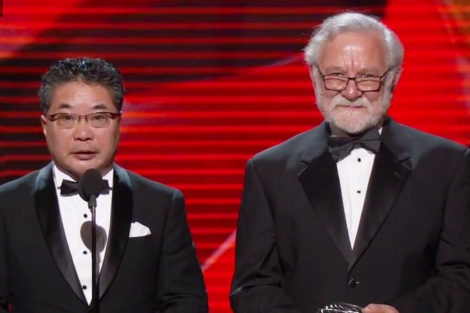

Kazutoshi Mori, PhD, a leading researcher at Kyoto University in Japan who has shared many major scientific awards with Walter, also received a 2018 Breakthrough Prize for his work on the unfolded protein response.

“As cell biologists, we decipher the fundamental principles of life,” Walter said while receiving the award at a Breakthrough Prize gala hosted by actor Morgan Freeman at the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif. “It’s a fascinating job to figure out how living cells accomplish these amazing tasks – and from that, we can learn what goes wrong in disease and what goes wrong as we age. Our work increases knowledge with the goal to reduce human suffering. I really thank the founders of this amazing award for shining the spotlight on the value of discovery.”

UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood said, “This is an exciting day for Peter Walter and for the University. Over the course of a research career spanning more than three decades, Peter has made seminal discoveries about cellular quality-control mechanisms and the diseases – from cancer to diabetes to Alzheimer’s disease – that may result if these basic processes go awry.

“His work is a perfect example of how decoding the basic principles of life can fundamentally improve our understanding of human health and the critical importance of such fundamental research to our society.”

The Unfolded Protein Response

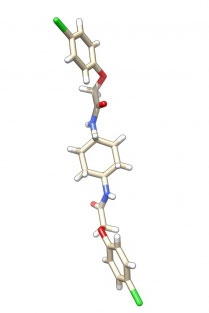

Proteins, the basic building blocks of the body, start out in the cell as simple, linear chains of amino acids that must be folded like origami into proper three-dimensional shapes before they can be sent off to do their job. Protein folding occurs within a maze-like structure called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which also serves as a checkpoint: well-folded proteins exit the ER and are shuttled to their destinations, but malformed proteins – a hallmark of many serious diseases – are targeted for destruction.

If too little ER is present to handle the number of proteins being synthesized – a state known as ER stress – a logjam of unfolded proteins accumulates. Working with yeast in his UCSF laboratory, Walter and colleagues discovered that sensor molecules in the ER membrane detect such stress and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), a suite of parallel signals that instruct genes to temporarily slow down protein synthesis while simultaneously increasing the abundance of ER.

But because accumulated unfolded proteins can be a menace, this compensatory role of the UPR has a built-in time limit: If a balance between ER abundance and protein synthesis cannot be restored quickly, the UPR shifts its signaling toward pathways that cause the cell to self-destruct.

Implications for Alzheimer's, Diabetes, and Other Diseases

Through either its cell-protective role or its promotion of cell death, the UPR’s life-or-death control in conditions of ER stress can cause disease.

In neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, for example, the UPR’s ability to facilitate protein synthesis may allow too many misfolded proteins to build up in brain cells, causing neural malfunction and memory loss. Likewise, the UPR may allow cancer cells that contain numerous mutant misfolded proteins to survive when they should not.

On the other hand, in retinitis pigmentosa, misfolded proteins push the UPR to induce self-destruction in the eye’s retinal cells, gradually robbing patients of their sight. Similarly, in type 2 diabetes, a continual demand for insulin may overwhelm the ER in the beta cells of the pancreas, which eventually succumb to UPR-induced cell death.

Walter’s most recent work centers around a molecule discovered in his laboratory called ISRIB.

The UPR is one arm of an overarching quality-control system known as the integrated stress response (ISR), and Walter and others have found that ISRIB (for “Integrated Stress Response InhiBitor”), which loosens the brakes the ISR puts on protein production, may reverse some of the cognitive deficits that follow traumatic brain injury.

Born in Berlin, Germany, Walter joined the UCSF faculty in 1983. He has been an HHMI investigator since 1997 and is the recipient of some of the most esteemed prizes in biomedical science. In 2014, Walter shared both the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award and the Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine with Kyoto University’s Kazutoshi Mori, PhD. Since 2016, he has been an executive committee member of the Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience at UCSF.

Since its inception in 2012, the Breakthrough Prize has awarded close to $200 million to honor paradigm-shifting research across fundamental physics, life sciences and mathematics. In addition to the $3 million Breakthrough Prizes, the selection committee also bestows up to three New Horizons in Physics Prizes and up to three New Horizons in Mathematics Prizes each year to early-career researchers, each with a $100,000 cash award.

Walter and his fellow laureates will be speaking Monday at the Breakthrough Prize Symposium, which is sponsored by UCSF, UC Berkeley and Stanford University. The symposium’s physical venue rotates among each university, with this year’s event taking place at Stanford and being broadcast live on Facebook.