Celebrating Seven Years of Science with TESS

by Adam Hadhazy

April 18, 2025, marked seven years since NASA's TESS took to the skies.

The Author

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has discovered far more than just alien worlds as it has scanned the stars in Earth’s celestial neighborhood.

April 18 marked seven years since NASA's TESS took to the skies. Although envisioned primarily as a seeker of new worlds, the spacecraft has proven to be a prolific discovery machine across many domains of astrophysics, building on its earlier accomplishments. As the years have gone by, TESS has witnessed quite a range of celestial phenomena. Just a few of the highlights include Earth-sized worlds in potentially habitable cosmic environs, stupendously powerful blasts of radiation, and stars getting ripped asunder by black holes.

“We’ve been very happy with all that TESS has accomplished over its scientific campaign that started - I can’t believe it - back in 2018!” says George Ricker, principal investigator for the TESS mission and a Senior Research Scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research (MKI).

Ricker’s history with TESS goes back nearly two decades to 2006, when he and colleagues drafted a proposal for a small, low-cost spacecraft that evolved into an approved NASA Explorer mission in 2013. MKI led the development and building of TESS, along with MIT's Lincoln Laboratory. This Fall, after having performed superlatively across its initial two-year primary mission and subsequent extensions, the spacecraft will inaugurate a third extended mission.

“TESS is showing zero signs of slowing down and we look forward to it continuing to reap scientific rewards for potentially many years to come,” says Ricker.

As a measure of scientific productivity, TESS has already generated nearly 2800 peer-reviewed studies. Impressively, Ricker points out that this rate of production is still upward-trending, bucking the usual leveling-off or tapering-down that many missions of similar length often experience. This past year for instance, TESS’ publication rate reached an average of two peer-reviewed papers per day. Illustrating the broad range of investigations that TESS data are enabling, roughly two-thirds of the studies are not even about exoplanets, the mission’s chief topic area.

TESS’ high discovery rate derives primarily from its enormous field of view, covering 2400 square degrees every single time it takes a sky image. This sky coverage equates to that of 12,000 closely packed full Moons. TESS snaps such huge sky shots more than 40,000 times per day. Ultimately, TESS is able to discern stars and galaxies that are 100,000 times fainter than the limit of the human eye. Because TESS’s orbit keeps it well away from Earth, the spacecraft can maintain this high (and reliable) efficiency rate during more than 95% of any given year.

Another major reason why TESS has spurred so much research is that all of the spacecraft’s data are made publicly available, and quickly; observations can be shared just a day or two after they were taken. Ricker says this spirit of scientific generosity has been integral to TESS. “Whenever I go to conferences or whatever, people always say ‘thank you’ for what we've done,” says Ricker. “It's something that's given us a lot of joy and excitement that we share TESS data with other people who find data useful.”

Planetary potpourri

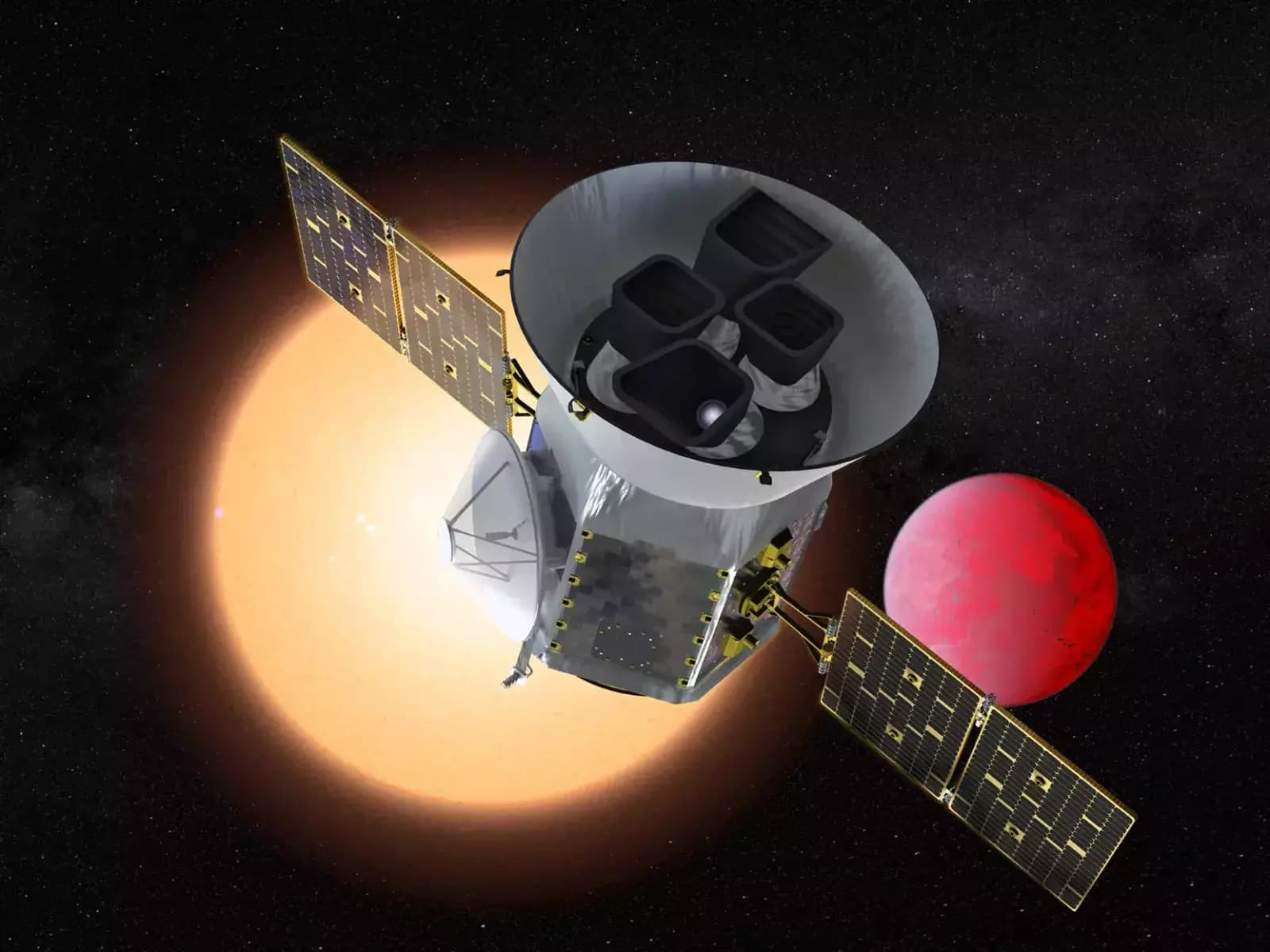

From its unique, elongated orbit beyond Earth’s radiation belts, TESS utilizes a quartet of sensitive cameras to observe roughly 200,000 of the nearest, brightest stars. TESS scrutinizes these stars for any periodic dimming events caused by planets transiting their faces, rather like moths flitting across a porch light. Using this technique, TESS has gathered signatures of more than 7600 potential planets, dubbed TESS Objects of Interest, or TOIs. To date, more than 600 TOIs have been confirmed as bona-fide worlds by follow-up observations.

Two of the most exciting exoplanets captured by TESS are exosolar system siblings, designated TOI-700 d and TOI-700 e. Discovered in 2020 and 2023, respectively, both worlds are approximately Earth-sized and orbit their star in the so-called habitable zone, the temperate region where liquid water could plausibly exist on the planets ’surfaces. Because their host star is only about 100 light years away, a mere cosmic stone’s throw, future observations could probe the worlds ’atmospheres for signs of life. “When we designed TESS, finding nearby planets like those at TOI-700 were a main motivation,” says Ricker.

Another just-discovered exoplanet stands as one of TESS ’biggest findings to date. Announced earlier this year, the world is apparently being disintegrated by its star, shedding the equivalent of a Mount Everest’s-worth of material roughly every 30 hours. “We think a planet just got too close to its host star, and what you actually see is there's a stream of gas and dust that's coming off and trailing behind the planet,” says Ricker.

Observations with JWST, a NASA flagship launched in 2021, have already been scheduled to perform spectroscopy on this shed material, discerning its makeup. Intriguingly, because the material is coming from the planet’s outer layers, researchers have a chance to see “inside” the planet over time and thus learn more about this alien world’s history. “In a way, you're dissecting the planet from the outside in,” says Ricker. “We’re really excited and surprised to have found this planet.”

Many more worlds, both promising and bizarre, are in store. Ricker estimates that as many as half of the 7000-plus-strong pool of TOIs will turn out to be genuine planets once confirmatory follow-up radial velocity observations are taken by ground-based instruments. These observations can rule out confounding phenomena, such as background binary stars, that masquerade as transiting worlds.

Validating many TOIs will require the next generation of telescopes, the biggest ever built, to collect enough light to give a final yay or nay. These mammoth new ‘scopes include the European Extremely Large Telescope, slated to debut next year. Keeping TESS operational will be key for precisely tracking potential exoplanets so those ground instruments can be pivoted to the right stars at the right time, Ricker says.

Beyond exoplanetary science

Over the last seven years, TESS has taken in a sizable haul of non-planetary bycatch while patiently maintaining watch for weeks at a time. Among the most notable and voluminous returns has been precision observations of stars’ brightness variations, caused by sound wave oscillations within stars. Those oscillations reveal details about the internal structure of stars, just like how seismic waves moving through Earth let scientists probe our world’s innards. In this way, TESS has been an incredible boon to asteroseismology, an aptly named field. “I think it's fair to say TESS has revolutionized asteroseismology,” says Ricker. “The number of asteroseismology papers from TESS alone is comparable to all asteroseismology papers going back to when the field first got seriously started in the 2010 time period.”

Another broad area in astrophysics benefiting from TESS is the study of “transients”— cosmic phenomena that are often bright and energetic but last mere moments. An example is tidal disruption events, or TDEs, when black holes gravitationally shred unlucky passing stars. Another is gamma ray bursts, or GRBs, which astoundingly pack as much energy into a few seconds as the Sun will make over its approximately 10-billion-year lifespan. Again, given its patient staring, TESS is excellent at serendipitously catching GRBs just as they’re ramping up. “We see the GRB event, and then we see its afterglow and the effect of shock waves and other ways in which it evolves,” says Ricker.

One recent and remarkable event was GRB 230307 which, as its designation implies, popped off in March 2023. This GRB is among the brightest ever captured in the roughly 50 years since the first GRB discovery. By seeing GRBs from their genesis, TESS is helping researchers learn more about the bursts’ progenitors, thought to be the mergers of compact objects such as neutron stars and black holes or possibly the cataclysmic demise of hefty stars.

In these ways and more, TESS has certainly lived up to its great scientific expectations. "TESS has provided us with a multitude of surprises," says Ricker, “and we look forward to celebrating many more TESS anniversaries."