Exploring Exoplanets

by Adam Hadhazy

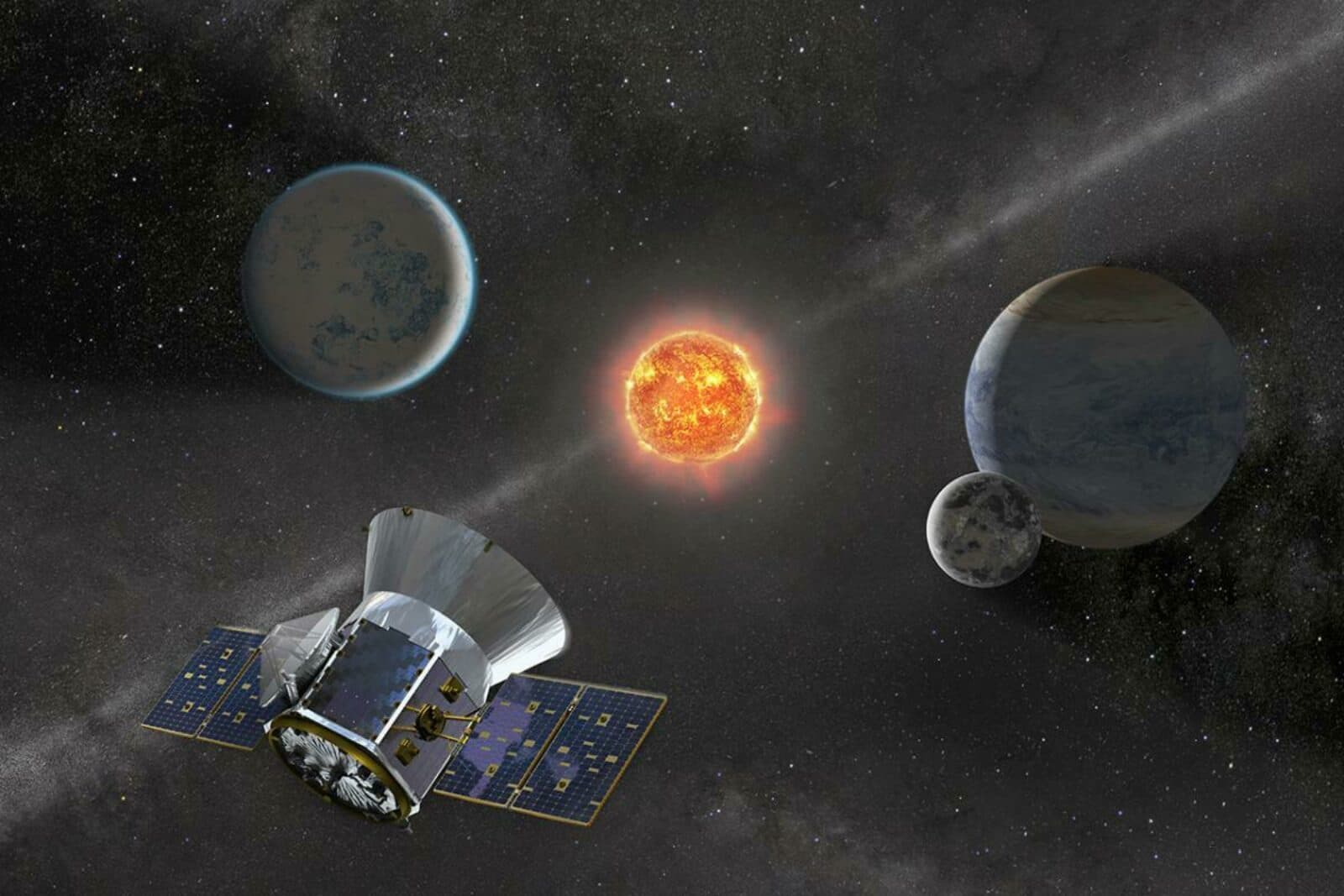

Celebrating a windfall of exoplanet discoveries—past, present, and future—by TESS

The Author

The Researcher

It's been two-and-a-half-years since the launch of NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and over that time, the plucky spacecraft has sure been busy. TESS has discovered 67 new worlds while racking up more than 2,100 that await subsequent, confirmatory observations. Beyond exoplanets, TESS has also captured quirky behavior in a long-studied kind of star, seen a star get gravitationally shredded by a black hole, and witnessed stars on the verge of exploding as supernovae.

TESS is far from finished. Having completed its two-year primary mission and observed three-quarters of the night sky so far, the spacecraft is now humming along in an extended mission. Overall, TESS will observe 200,000 of the nearest, brightest stars, looking for telltale, periodic dips in starlight that reveal the presences of exoplanets as they transit across their stars' faces. The planets TESS finds will be among the easiest to deeply study and characterize with the next generation of telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Those telescopes and others will probe the worlds' atmospheres for so-called biosignatures—cocktails of gases that could only be plausibly put there through the activities of alien life.

The Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology led the development of TESS, along with MIT's Lincoln Laboratory and NASA. The efforts have certainly paid off, with the highly successful primary mission now in the rear view and much more science yet to come.

"It’s a wonderful feeling to have completed the primary mission," says George Ricker, the principal investigator for the TESS mission and a Senior Research Scientist Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research (MKI). "The TESS spacecraft and cameras operated fully as planned, and the operations and science teams have done a fabulous job of analyzing the data for public use."

From both scientific and operational perspectives, the spacecraft has indeed performed admirably, with nary a hiccup, despite its modest (for a space mission) $200 million price tag.

"The TESS satellite itself has responded beautifully in orbit, despite its relatively low cost," says Ricker. "It's as if a Gran Prix racer was somehow constructed at the price of a Prius!"

Among the highlights of TESS' exoplanetary haul to date has been the first intact world around a white dwarf star, the shrunken remnant of a star like our Sun (and which our Sun will turn into in circa five billion years). TESS also found an ultrahot Neptune-like planet orbiting so closely to its host star that it could not have plausibly formed there. That scorched world supports the theory that planets can move around considerably within their solar systems over time. Odder still, TESS has bagged what Ricker describes as a "naked Earth-sized planet, with no detectable atmosphere." Another puzzling outlier: the most massive Neptune-sized world to date which, although it should be mostly made of low-density gas, has a density comparable to our rocky planet.

More treasures like these should be in the offing over the next couple years as TESS scans even more sky and performs revisits of the northern and southern hemispheres' skies, hoovering up important follow-up data. The revisits will enable comparison against TESS' original images of stars and possible planetary transits. That comparison will be necessary to suss out smaller exoplanets with decently long orbital periods—the kinds of worlds, like ours, that could be amenable to life.

As the mission has gone on, Ricker and colleagues have honed TESS' searching abilities, remotely reprogramming the processor onboard and modifying the science ground operations and data pipelines. That means TESS' extended mission will likely be significantly more fruitful than the primary mission.

"We expect the TESS data taken with our new science modes to reveal even more Earth-sized planets as 'golden targets' for follow-up studies by NASA's Webb and Roman space telescopes," says Ricker.

While TESS is primarily staring at that aforementioned set of 200,000 stars, it is also gathering a background view of more than 100 million potential host stars. Thorough analyses of those images could yield perhaps 100,000 new exoplanet discoveries, or 20 times more than currently known.

Suffice to say, it’s exciting times for the TESS researchers and the field of exoplanetary science in general.

"The path is now clear," says Ricker, "to our accomplishing all of the new goals for TESS that were hoped for."