Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope Discovers Slew of New Pulsars

(Originally published by the Stanford Linear Acclerator Center)

January 7, 2009

Four months into its mission, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has discovered 12 never-before-seen pulsars and observed gamma-ray pulses from 18 others, shedding new insight on the high-energy universe.

"I am very happy to welcome you all to a new era in pulsar physics," Roger Romani said at a press conference held yesterday at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Long Beach, California. Romani is a researcher in the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. "We know of 1800 pulsars, but until Fermi we saw only little wisps of energy from all but a handful of them. Now, for dozens of pulsars, we're seeing the actual power of these machines."

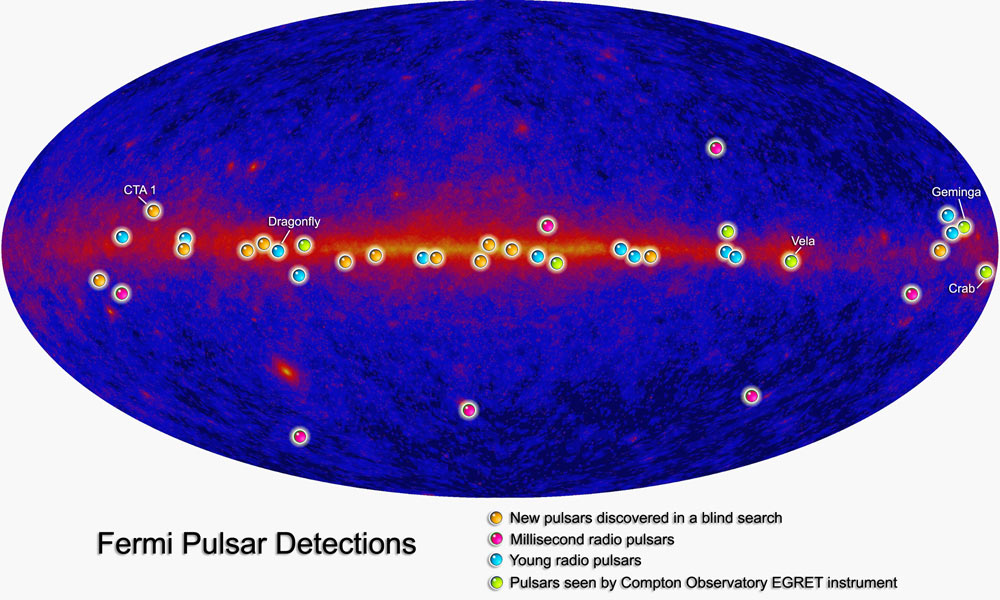

The Fermi Telescope has found 12 previously unknown pulsars (orange). It also detected gamma-ray emissions from known radio pulsars (magenta, cyan) and from known or suspected gamma-ray pulsars identified by NASA's now-defunct Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory (green). (Image courtesy of NASA/Fermi/LAT Collaboration.)

In the past, most pulsars—rapidly spinning neutron stars that emit energy in narrow beams—were observed only in radio waves. Yet, as the FGST data reveals, this radio-wave emission is extremely weak compared to the pulsars' flashes of gamma-rays.

The 12 newly discovered pulsars offer insight into the mechanism behind the gamma-ray emissions. The data show that the classic understanding of emission, whereby gamma rays are created in the same location as radio waves, is mistaken. Researchers now theorize that the radio beams form near the neutron star's surface, while the gamma rays form far above.

FGST is also shedding light on pulsars as they near the end of their lifecycles. Over the past few months, the telescope found seven very old and relatively rare pulsars that are thought to have gravitationally attracted additional stellar matter from companion stars, causing them to increase in mass and spin much faster. These "millisecond" pulsars spin hundreds of times faster than their younger siblings, with their surfaces moving at up to a tenth of the speed of light. They also have magnetic fields 10,000 times lower and are thought to be 10,000 times older than previously discovered pulsars.

With the observation of these millisecond pulsars, Romani said, "we're really seeing the history of pulsars." Alice Harding of the NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center added: "This is the tip-of-the-iceberg. We'll probably be discovering a lot more."

Researchers announced these findings at the American Astronomical Society meeting this week in Long Beach, California, and at the Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics last December in Vancouver, Canada. More information can be found in a NASA press release issued yesterday and in a recent Science News article by Ron Cowen.

Press release may be found here.