Platinum-Coated Nanoparticles Could Power Fuel Cell Cars

(Originally published by Cornell University)

December 8, 2010

Fuel cells may power the cars of the future, but it's not enough to just make them work -- they have to be affordable. Cornell researchers have developed a novel way to synthesize a fuel cell electrocatalytic material without breaking the bank.

The research, published online Nov. 24 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, describes a simple method for making nanoparticles that drive the electrocatalytic reactions inside room-temperature fuel cells.

Fuel cells convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy. They consist of an anode, which oxidizes the fuel (such as hydrogen), and a cathode, which reduces oxygen to water. A polymer membrane separates the electrodes. Fuel cell-powered cars in production today use pure platinum to catalyze the oxygen reduction reaction in the cathode side. While platinum is the most efficient catalyst available today for the oxygen reduction reaction, its activity is limited, and it is rare and expensive.

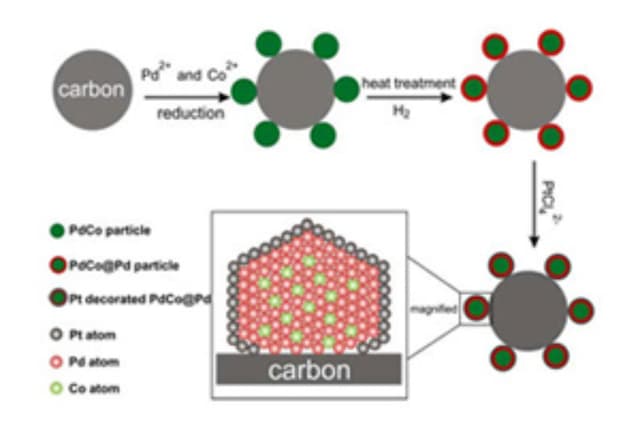

The Cornell researchers' nanoparticles offer an alternative to pure platinum at a fraction of the cost. They are made of a palladium and cobalt core and coated with a one-atom-thick layer of platinum. Palladium, though not as good a catalyst, has similar properties as platinum (it is in the same group on the Periodic Table of Elements; it has the same crystal structure; and it is similar in atomic size), but it costs one-third less and is 50 times more abundant on Earth.

Researchers led by Héctor D. Abruña, the E.M. Chamot Profesor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, made the nanoparticles on a carbon substrate and made the palladium-cobalt core self-assemble -- cutting down on manufacturing costs. First author Deli Wang, a postdoctoral associate in Abruña's lab, designed the experiments and synthesized the nanoparticles.

David Muller, professor of applied and engineering physics and co-director of the Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science, led the efforts geared at imaging the particles down to atomic resolution to demonstrate their chemical composition and distribution, and to prove the efficacy of the catalytic conversions.

"The crystal structure of the substrate, composition and spatial distribution of the nanoparticles play important roles in determining how well the platinum performs," said Huolin Xin, a graduate student in Muller's lab.

The work was supported by the Energy Materials Center at Cornell, a Department of Energy-supported Energy Frontiers Research Center. Researchers also used equipment at the Cornell Center for Materials Research.