Materials Scientists Learn How Mother of Pearl is Made

(Originally published by Cornell University)

Dec 4, 2015

Mother nature has a lot to teach us about how to make things.

With that in mind, Cornell researchers have uncovered the process by which mollusks manufacture nacre – commonly known as “mother of pearl.” Along with its iridescent beauty, this material found on the insides of seashells is incredibly strong. Knowing how it’s made could lead to new methods to synthesize a variety of new materials with as yet unguessed properties.

“We have all these high-tech facilities to make new materials, but just take a walk along the beach and see what’s being made,” said postdoctoral research associate Robert Hovden, M.S. ’10, Ph.D. ’14. “Nature is doing incredible nanoscience, and we need to dig into it.”

Hovden is lead author of a paper describing the discovery published in the Dec. 3 edition of the journal Nature Communications. Hovden worked with Lara Estroff, associate professor of materials science and engineering; David Muller, professor of applied and engineering physics; graduate student Megan Holtz; and Stephan Wolf, a visiting scientist from Germany, in Estroff’s Bio-Inspired Materials Research Group.

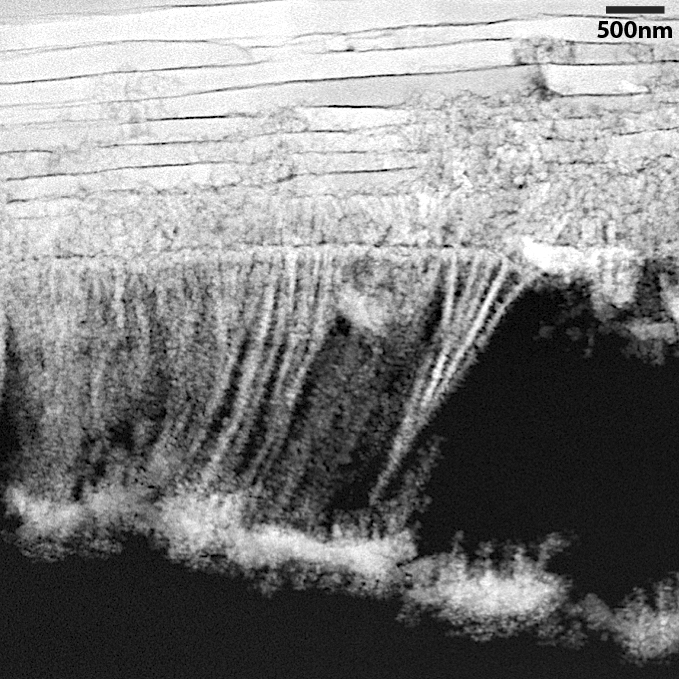

Using a high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM), the researchers examined a cross section of the shell of a large Mediterranean mollusk called the noble pen shell or fan mussel (Pinna nobilis). To make the observations possible they had to develop a special sample preparation process. Using a diamond saw, they cut a thin slice through the shell, then in effect sanded it down with a thin film in which micron-sized bits of diamond were embedded, until they had a sample less than 30 nanometers thick, suitable for STEM observation. As in sanding wood, they moved from heavier grits for fast cutting to a fine final polish to make a surface free of scratches that might distort the STEM image.

Images with nanometer-scale resolution revealed that the organism builds nacre by depositing a series of layers of a material containing nanoparticles of calcium carbonate. Moving from the inside out, these particles are seen coming together in rows and fusing into flat crystals laminated between layers of organic material. (The layers are thinner than the wavelengths of visible light, causing the scattering that gives the material its iridescence.)

Exactly what happens at each step is a topic for future research. For now, the researchers said in their paper, “We cannot go back in time” to observe the process. But knowing that nanoparticles are involved is a valuable insight for materials scientists, Hovden said.

Estroff’s lab is supported by the National Science Foundation, and the work made extensive use of the microscopy facilities in the Cornell Center for Materials Research. The work also is supported by the Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science. Frédéric Marin of the Université Bourgogne - Franche-Comté provided the sample shells.