Mouse Studies Offer New Insights About Cocaine’s Effect On the Brain

(Originally published by The Rockefeller University)

February 15, 2017

Cocaine is one of the most addictive substances known to man, and for good reason: By acting on levels of the “feel-good” chemical dopamine, it produces a tremendous sensation of euphoria.

Now the laboratory of Rockefeller University Professor and Nobel Laureate Paul Greengard has shown for the first time in mice how a protein called WAVE1 regulates the brain’s response to cocaine. Their discovery, which was published recently in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers fundamental insights into the brain’s inner workings—and could lead to better interventions for treating addiction to cocaine and other drugs.

Cocaine and the brain

Researchers have long used cocaine as a model to study how certain messages are transmitted in the brain. And Greengard’s group, which investigates the molecular basis of communication between nerve cells in the brains of mammals, has studied WAVE1, a protein involved in cell signaling, for more than a decade. But their PNAS study reveals something new about the way in which WAVE1 and dopamine interact.

“We knew about the connection between WAVE1 and dopamine many years ago, but until now no one knew the mechanism of how cocaine stimulates WAVE1 and how WAVE1 regulates cocaine’s actions,” says Yong Kim, a Research Assistant Professor in Greengard’s lab and the senior author of the new study.

No WAVE1, no reward

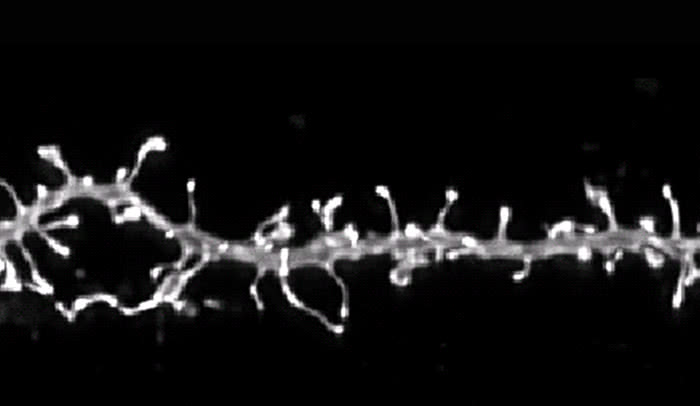

In the new work, the team observed that WAVE1 became active in the brain of mice exposed to cocaine, and that this cocaine effect on WAVE1 could be prevented by blocking dopamine receptors. The research also provides new clues about how WAVE1 influences changes in the brain’s synapses— the junctions between nerves through which impulses pass—in response to cocaine exposure.

Specifically, the investigators looked at changes in an area of the brain called the nucleus accumbens, a key component of the neural reward system that is known to play a critical part in addiction—and in which dopamine is heavily involved. When these synapses form, they allow the signals from dopamine and another neurotransmitter called glutamate to be transmitted.

To investigate the interaction between WAVE1 and dopamine more specifically, the team looked at mice that had WAVE1 selectively removed in nerve cells. These nerve cells also contained one of the subtypes of dopamine receptor (called D1). They found a significant decrease in the preference for cocaine in these mice, compared with those producing normal WAVE1 levels. This suggested that the dopamine signals were not being transmitted.

However, this effect was not seen when WAVE1 was removed from nerve cells containing a different dopamine receptor subtype (called D2). Those results suggest previously unknown details about how cocaine works.

Addiction intervention

“It’s well known that cocaine increases the signaling of dopamine in the brain,” Kim says. “Understanding more about the mechanism of cocaine action is providing new insight into the neurobiology of addiction. Our eventual goal is to use these findings to find a way to develop a drug to treat addiction.”

However, Kim says there are limitations to the current work, largely because the mice were injected with cocaine by the researchers. Future studies will need a system in which the mice can self-administer the cocaine by pushing a lever and injecting themselves, a model that more closely mimics human addiction behavior.

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Defense (USAMRAA W81XWH-09-1-0392 and W81XWH-09-1-0402), the National Institutes of Health (DA010044, MH090963, R01DA014133 and NS34696), and the JPB Foundation.