Neuroscience Around the World

by Lindsay Borthwick

Neuroscience and neurodata have no borders

The Author

October is an important month for brain researchers. They flock to an annual conference organized by the Society for Neuroscience to share new findings, exchange ideas and get a pulse of what’s happening in the field. This year’s event, in Chicago, welcome about 25,000 neuroscientists from all over the world. Some of the latest findings are captured in this month’s neuroscience roundup, which takes us from the rainforests of Costa Rica, where Rockefeller’s Daniel Kronauer snapped an award-winning photo of a superorganism, to Seattle, where Allen Institute researchers released a massive dataset for brain researchers globally. It is built to be shared, using the award-winning Neurodata Without Borders data format, similar to the way Unicode allows us to share emojis.

- Neurodata Without Borders wins R&D100 Award

“There are a vast number of neurons in this dataset whose activity has never been seen by a human eye. These data are unprecedented — and we’re releasing them publicly and in a standardized format so that anybody on the planet can use them for their own discovery.”

—Christof Koch, Ph.D., Chief Scientist and President of the Allen Institute for Brain Science,

commenting on the release of a new resource for brain researchers worldwide.

Allen Institute scientists made the recordings with a new kind of electrode, or sensor, called Neuropixels, which allowed them to listen into the crosstalk between hundreds of cells at the same time. But making the recordings in live mice was just part of the challenge. The massive dataset also had to be collected and packaged so it could be shared. That is why the researchers used a standardized data format known as Neurodata Without Borders, which was created by a consortium of researchers and foundations, including The Kavli Foundation, to solve the data-sharing problem in neuroscience and accelerate progress in the field. Neurodata Without Borders was recognized this month with a 2019 R&D100 Award from R&D Magazine, which recognizes R&D pioneers and revolutionary ideas in science and technology.

- A cathedral of cooperation

Photo by Daniel Kronauer; used with permission.

This striking image of a nest of army ants earned biologist Daniel Kronauer top honors in the prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition, organized by the Natural History Museum in London. The cathedral-shaped structure is actually temporary, constructed nightly be the colony of about 100,000 army ants, which link their bodies together to form a scaffold. The shot was a risky one. Army ants are venomous. A whiff of carbon dioxide from Kronauer, who was crouching nearby with his lens trained on the nest, would have sent them into a frenzy. Kronauer is a professor at The Rockefeller University and a member of the Kavli Neural Systems Institute, where he studies social evolution and behavior with complex societies, such as ant colonies. He snapped the photo in the rainforest of Costa Rica, where he was conducting field work to learn more about army ants, including what species they prey on and how they interact with arthropods that live within the ant colony.

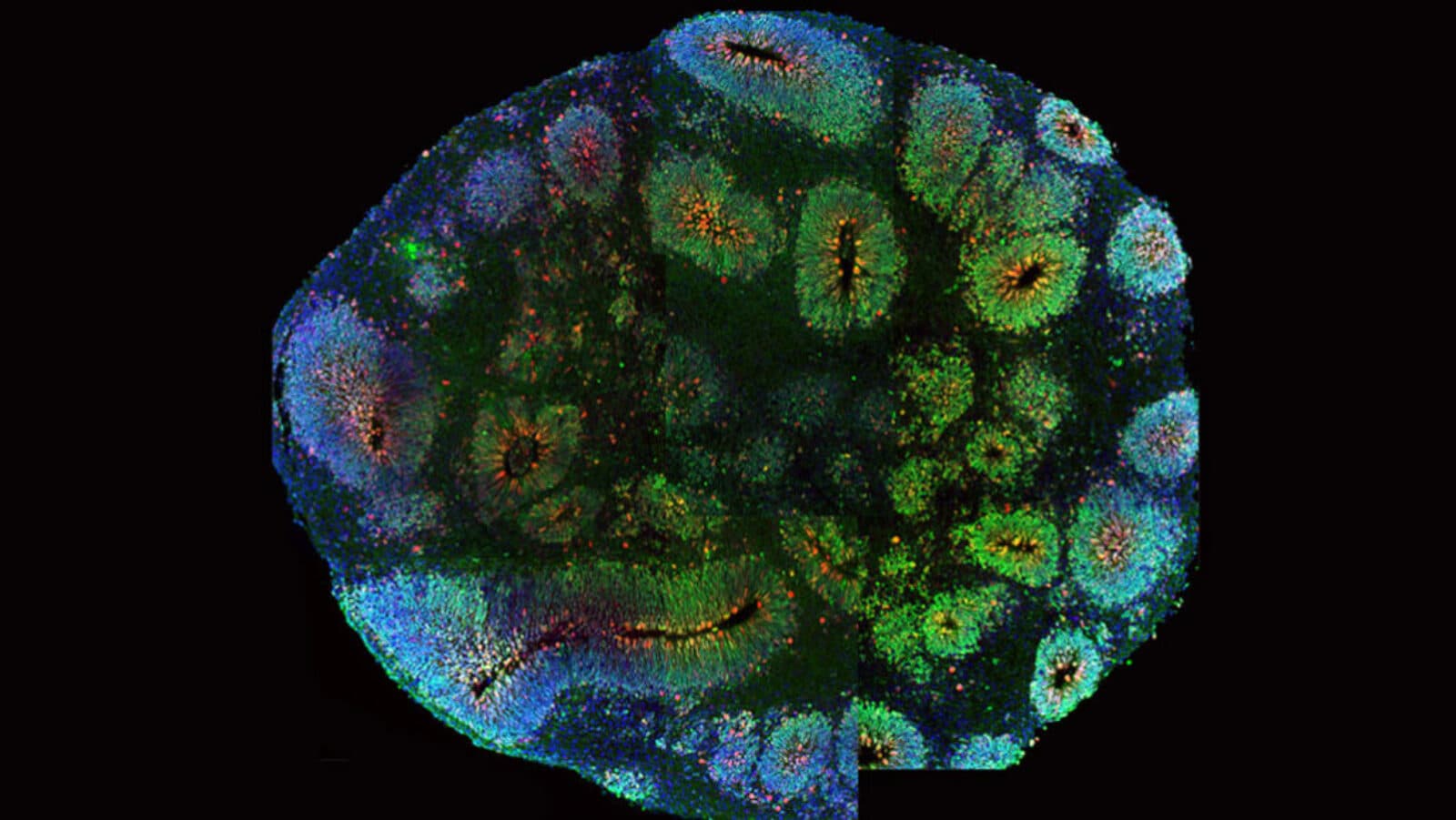

- Stressed out mini brains

Mini brains, or clusters of neurons grown from stem cells in the lab, have been having a moment. Over the past few months, we’ve written about mini brains recapitulating the brain activity of the developing human brain, mini brains in space, and more, underscoring their growing popularity as a research tool. Now, new findings presented at the Society for Neuroscience meeting, highlight their limitations as a model for human brain development. Arnold Kriegstein—a member of the Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience—and his team at the University of California, San Francisco, compared brain cells taken from organoids with those from human brain tissue. They found that the neurons from organoids exhibited signs of stress and sometimes didn’t resemble any of the well-categorized cells types in the brain. The findings are a reality check for scientists.

“There’s been a lot of hype,” about brain organoids’ potential,” neuroscientist Michael Nestor of the Hussman Institute for Autism in Baltimore, told Science News. “I’m excited too, but we’ve got to take a step back. I think this work does that.”

- Dueling brain waves

A whole lot happens in the brain while we sleep—including a high-stakes duel. During sleep, two distinct patterns of sleep waves take over, sweeping across the brain and influence how well an organism remembers a new skill learned the previous day. It’s a form of mental replay that is essential to making memories. A new study, led by Karunesh Ganguly of the University of California, San Francisco, turned down the activity of specific types of brain cells in rats, effectively suppressing one type of sleep wave or the other. Interfering with the waves either protected the rats’ ability to remember or led them to forget the task they had learned earlier on.

“We believe these two types of slow waves compete during sleep to determine whether new information is consolidated and stored, or else forgotten,” Ganguly said in a statement. Understanding the interplay between these sleep waves has implications for boosting human memory or forgetting traumatic events, according to Ganguly, who is a member of the Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience at UCSF.

- Remembering, again

A core symptom of schizophrenia has been reversed in mice engineered to mimic the brain disorder. Researchers at Columbia University, including Stavros Lomvardas, who is a member of the Kavli Institute for Brain Science, have restored working memory, the ability to retain and recall information on the fly, in mice using a drug that is in early stage clinical trials for leukemia and other forms of cancer. The drug indirectly inhibits the activity of a gene the researchers called a “multitasker.” Schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects 21 million people worldwide and causes symptoms like paranoia, auditory hallucinations and delusions. But memory problems are also a core symptom—and one that has been particularly hard to treat. When the researchers administered the drug, the mice’s working memory improved dramatically; the researchers also saw cellular changes in the prefrontal cortex of the brain—the seat of working memory—suggesting the drug was affecting the molecular mechanism underlying the memory problems.