Seeing the Cosmos Anew with the Prime Focus Spectrograph

New instrumentation from the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe will help scientists study the early history of the universe

It’s finally primetime for the Prime Focus Spectrograph (PFS). Some 15 years after researchers first began drawing it up, this powerful astronomical instrument is now set for its first night of science operations on March 27, 2025.

For Masahiro Takada, who has worked on PFS since the project’s inception in 2010 as co-chair of science working groups, it’s been a day long in the making. “So 15 years . . . you know, my hair started turning gray!” he jokes. “But the instrument is working very well, and this means a lot to us.”

Takada is Deputy Director of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU, WPI) at the University of Tokyo, one of the lead organizations that proposed and developed the $100 million-plus PFS instrument, as well as planned its ambitious large-sky survey. For that observing campaign, from a perch within the Subaru Telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, PFS will peer back through 10 billion years in cosmic history. Plumbing the cosmic depths in this way will allow researchers to gain new insights into the formation and evolution of galaxies across most of the Universe’s existence, in turn helping to pry open secrets about the fundamental makeup of the cosmos and how it has matured.

“We have really big questions we’re hoping to answer,” says Takada. “PFS will be a key part of trying to find solutions to problems in astrophysics and cosmology.”

Coloring in the dark

By tracking the growth and distribution of millions of galaxies, PFS will shed light on dark matter and dark energy—literally two of the biggest mysteries in all of science. The former, dark matter, is the name for the little-understood material that comprises about a quarter of the composition of the Universe, outnumbering the ordinary matter we perceive some five times over. Dark energy—an even less-understood, pervasive energy field—encompasses the remaining lion’s share of the Universe and is driving its accelerating expansion, according to cosmologists’ most stringent theories.

Putting those theories to the test is a primary goal of PFS as it conducts about a full year’s-worth of nightly observing runs over the next several years. As a spectrograph, PFS relies on prism-like optics to split received light apart into constituent “colors” or wavelengths. PFS conveys this precious cosmic light via fiber optic cables, numbering nearly 2400 in total. Every single fiber is capable of observing an individual cosmic object of interest, from distant galaxies to nearby stars in our own Milky Way Galaxy and galactic neighbors.

PFS brings together these attributes to Subaru, one of the world’s largest telescopes with an 8.2-meter primary mirror that affords immense light-collecting power. More light means fainter, more distant objects can come into view, enabling PFS to probe deeper into space and time. Subaru also boasts a tremendous field of view that measures 1.3 degrees, or nearly three times the diameter of the full Moon, soaking in a wide swath of firmament. Colors-wise, PFS can see the full spectrum of visible light, plus a band of infrared light out to 1.26 micrometers (millions of a meter) in wavelength. That infrared sensitivity is an important feature that lets researchers calculate the velocity of individual galaxies whose visible starlight has been redshifted by the expansion of the universe into the infrared range.

In combination, these characteristics will push observational astronomy into new territory. “PFS is very powerful,” says Takada. “With it, we can deeply and densely sample the sky.”

Technical marvel

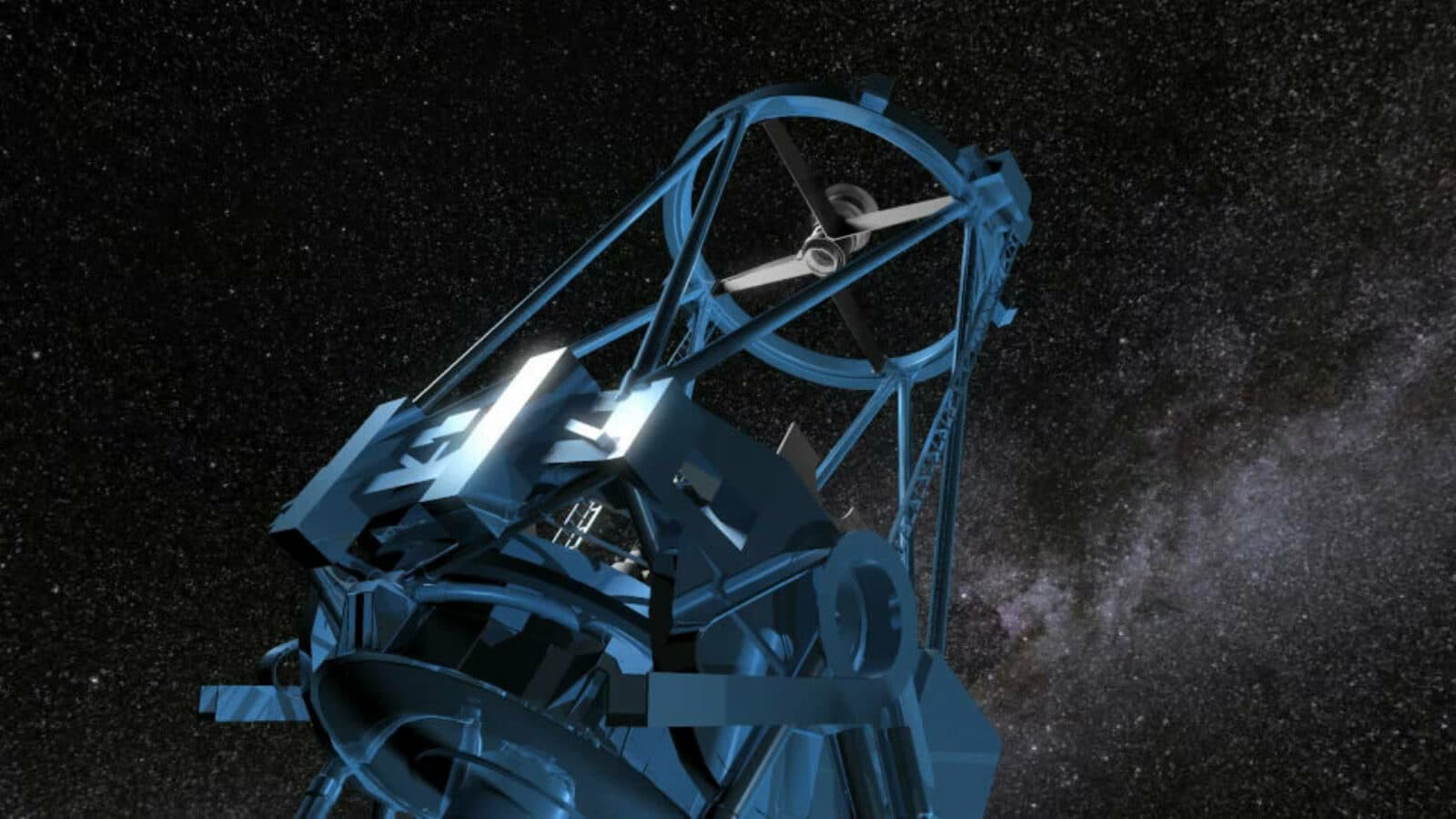

Arriving at this moment of scientific prowess required years of technical advances and successes. One prominent challenge that PFS designers faced is that Subaru is a multi-use astronomical workhorse; not all of its science operations would benefit from a spectrograph instrument placed at the telescope’s prime focus, the point where light from the primary mirror converges. As such, PFS builders had to design the instrument to be removable.

That proved to be no small feat for the main PFS instrument, which is a large tube weighing three tons and about three meters tall, containing the fibers, optics, and other equipment. A robotic device hoists this main instrument for swap-outs at Subaru, expected to happen every few weeks. When installed, the main instrument’s 2400 fibers—which are bunched into 84 tubes each containing about 30 fibers—must be reconnected to the rest of the instrument. “It’s like plugging a big cable in,” Takada says.

Getting the fibers trained on exactly the cosmic object of interest involves star-tracking cameras and a mixture of automated guidance and manual inputs from researchers to point at just the right spot on the sky. “There’s no address, like ‘215 Chestnut Street’” for cosmic objects, Takada jokes. “You have to calculate all the coordinates.”

To achieve the exact pointing, the fibers are precision-controlled by high-tech positioners to a specificity of 20 micrometers; for a comparison, Takada points out this lilliputian span is about 1/5th of the diameter of a Japanese person’s average strand of hair. “On PFS, we manage to control all these fibers simultaneously to that level of precision,” he says. Amazingly, this many-target acquisition and fiber positioning usually takes about two minutes to complete for a given observing run.

The well-traveled cosmic light that streams through PFS’s fibers is funneled into a platform of four spectrograph modules, where the light is bounced around and split apart into three small tubes colored blue, red, and purple, representing high-energy visible light, low-energy visible light, and even-lower-energy infrared light, respectively. The spectra generated in this process reveal much about the composition of the observed object, as well as its speed and direction.

For probing nearby stars in our Galaxy and others, as well as the material in the intergalactic medium, the stew of material not locked up in stars, this work will propel one of PFS’ science themes of galactic archeology. By “digging back” into the dynamic and compositional histories of nearby galaxies, PFS will help constrain the role of dark matter, which appears to act like a sort of scaffold for normal, visible matter to glom onto. Of chief interest will be the Milky Way’s array of dwarf galaxies.

“We know that dwarf galaxies are dark-matter-dominated systems,” says Takada. “By carefully studying them with PFS, we’ll learn a lot about dark matter’s nature.”

Unbounded discovery

The total scope of intended science with PFS is vast, including assessing the mass of the famously aloof, wisps of particles known as neutrinos, along with testing Albert Einstein’s watershed theory of general relatively. Besides forging ahead with its own discoveries, though, a critical component of PFS’ mission will be to complement other instruments and bolster any discoveries they may make. Replication is essential to science; if other researchers cannot duplicate or otherwise support another group’s results, then those results cannot be considered valid.

Astrophysics is no exception. One of the biggest findings in the field’s history, the discovery of dark energy in the late 1990s, came about from two independent teams jointly announcing their stunning observations of distant supernovae that appeared much fainter than expected.

In the case of PFS, such confirmatory work is likely to be building upon hints of what researchers refer to as time-evolving dark energy. Recent large-scale surveys such as DESI (pronounced “daisy,” for Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, another Kavli astrophysics institute-associated project), have suggested that dark energy has changed over cosmic history, reflected in a varying rate of expansion for the Universe. Such a discovery could be paradigm-shifting, says Takada, and would naturally require an independent experiment to lend support. “If the DESI finding is true that there is time-evolving dark energy, PFS should be able to find the same thing to confirm with a longer lever arm, so to speak,” says Takada. “Our surveys are quite complementary to each other.”

As PFS, DESI, and other future instruments open the cosmicscape as never before, Takada looks forward to the possibility of glimpsing something entirely new. “Even more exciting would be some discovery we didn't expect with PFS,” Takada says. “The Universe has never stopped surprising us.”