Synthetic Blood Vessels Could Lead to Breakthroughs in Tissue Engineering

(Originally published by Cornell University)

May 29, 2012

Human tissue, be it in the heart, brain or bones, can't function without a vascular system -- the intricate network of vessels that circulate life-sustaining blood and nutrients. And it's notoriously hard to introduce vascularization into synthetic tissue for use in regenerative medicine, like tissue replacement surgery.

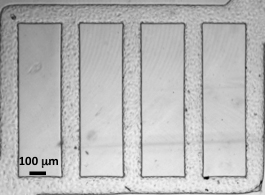

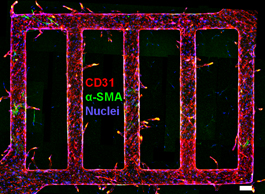

Enter Cornell engineers, taking an engineer's approach to making synthetic blood vessels. They've designed tiny, 3-D microchannels in a soft biomaterial and injected human umbilical vein endothelial cells into the channels. They embedded tissue cells from the brain into the surrounding gel and watched the interactions between the "vessels" and cells, which commonly surround microvessels in the body.

Signals from these tissue cells led to new blood vessels sprouting from the originals -- a living network of blood vessels engineered completely in vitro.

The results, which could lead to new techniques in regenerative medicine and better drug delivery strategies, are from the lab of Abe Stroock, associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and member of the Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science.

The work is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences May 28.

Such live, in-vitro microvessels could be a step toward developing human tissues both to study biological processes in the lab and to serve as replacement tissues for implantation into the body during surgery.

"The hope is we can start with something this simple, and the cells will then grow into the capillary structures and higher order vessel structures required for a fully deployed vascular system," Stroock said.

The researchers also experimented with mimicking diseases like cancer or thrombosis in the vessels by infecting them with certain compounds or proteins known to promote vessel growth or create an inflammatory response.

In a collaboration with the Jose Lopez lab at the Puget Sound Blood Center, the researchers showed that healthy vessels proved to be a good, non-sticky interface for transporting blood smoothly, even around corner vessels, which are traditionally where blockages due to disease occur. The researchers found that when the vessels were treated with an inflammatory compound, they became thrombotic -- similar to when real vessels become inflamed.

To further inform their study, the researchers collaborated with Claudia Fischbach-Teschl, associate professor of biomedical engineering, who studies how tumors grow. A signaling protein called VEGF, when added to the microvasculature, led to development of new blood vessels sprouting from the originals -- a hallmark of how tumors grow.

"One of the evil geniuses of tumors is knowing how to grow new vasculatures," Stroock explained.

He said he was interested in developmental vascular biology from an engineer's perspective because of the hypothesis that physical flow informs the development of microvessels even from an embryonic stage. In order to understand how a simple grid of tubes in a placenta transforms into the geometry of the microvasculature in humans, it is important to understand how the physical environment influences these initial vessels, he said.

"The mechanics of the flow play a central role in defining what the network will be," Stroock said.

The paper's first author is Ying Zheng, a former postdoctoral associate who is now at the University of Washington in Seattle. The work at Cornell was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the Cornell Center on the Microenvironment and Metastasis, Human Frontiers in Science Programme, the New York State Division of Science, Technology and Innovation, and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.