The Hopes and Fears Lab

Meaningful conversations about science in 15 minutes

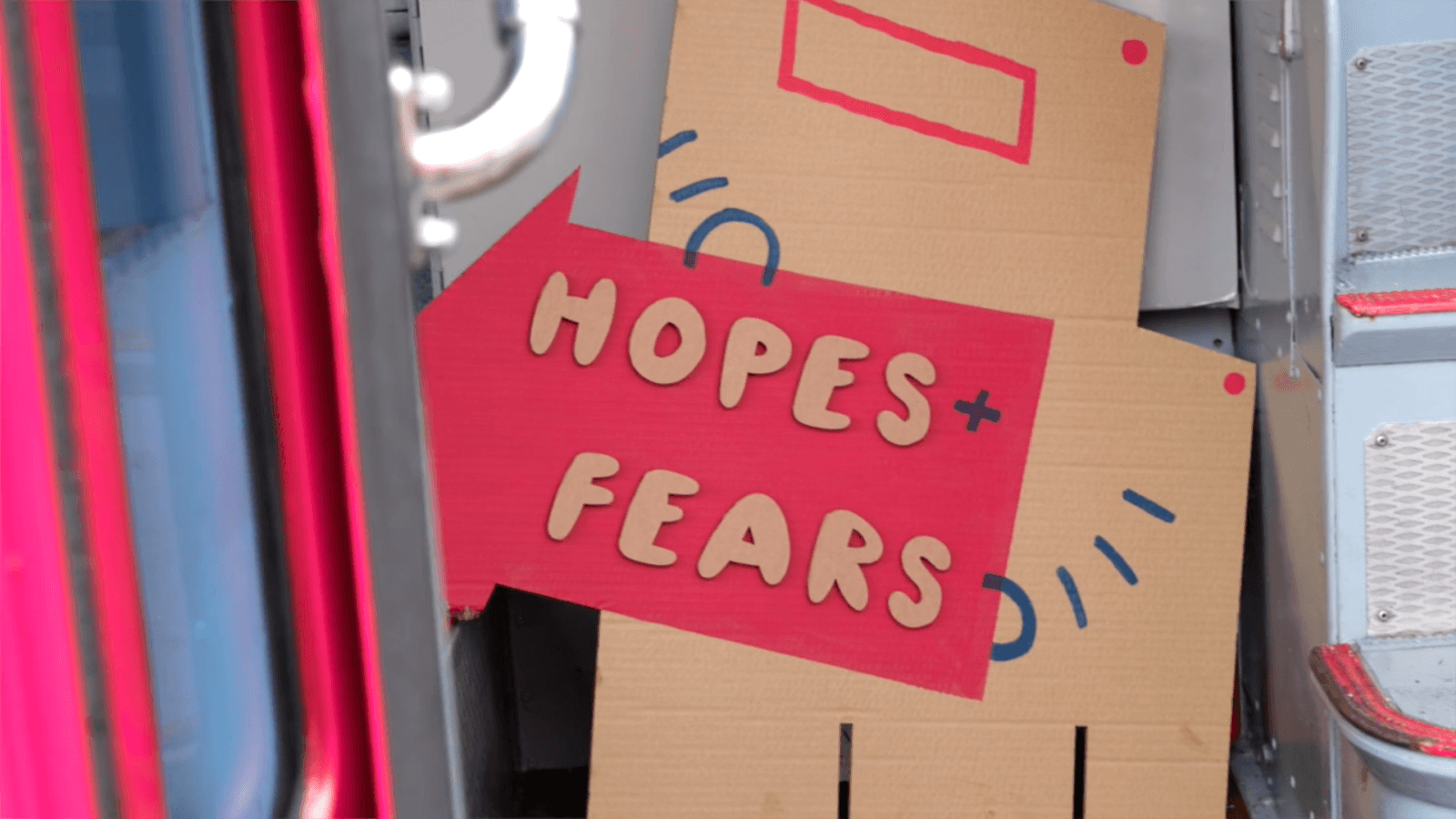

Picture two red, double-decker buses rolling into a park in Cambridge, England. They have bright signage about artificial intelligence and how it has become, and will continue to be, part of our everyday lives. Aboard the buses are AI researchers each sitting at a table with a 15-minute hourglass timer and a pad of paper. No research slides or prepared talks, but a willingness to chat with interested passersby about their work. It’s called The Hopes and Fears Lab.

“I tend to call it a conversation experiment,” says Catherine Galloway, Innovation and Translation Lead at the Kavli Centre for Ethics, Science, and the Public at the University of Cambridge.

The Hopes and Fears Lab, as Galloway explains, was inspired in part by an international organization called The Human Library. In that project, founded in Denmark, people can “check out” people rather than books, sit down with them, and learn more about their remarkable lives. She thought, what if we could do this with scientists, and focus the conversation on our shared hopes and fears for the future?

She and her team set out designing every facet of the experience, from welcoming people into the space, reducing barriers for participating, and allowing different levels of engagement – whether someone wants to read the information panels, take a postcard home, or sit down and actually converse with a scientist. The Hopes and Fears Lab isn’t always aboard double-decker buses; the team has also hosted pop-ups in community centers. But regardless of the location, the goal is the same: to create a welcoming environment that invites open dialogue about what we all collectively want and need for both scientific research and for society as a whole. In this Lab, discovery science is the starting point but not the final destination.

The team worked with artist Tom McLean who devised a look and feel using bold red and blue colors and bespoke characters painted on cardboard. Galloway explains, “His idea was, ‘It needs to be pop up. It needs to be sustainable, and it needs to not look like it's owned by anybody. It has to be a different space for everyone.”

Now they needed scientists. In recruiting volunteers, Galloway found that the researchers she spoke to were interested in public engagement generally but nervous about spending two hours speaking to a wide variety of strangers, especially without slides or a poster to point to. But the format, with a time constraint and a friendly atmosphere, set the interactions up for success, and Galloway and her team worked with the volunteer scientists beforehand to practice speaking about their work in an accessible way while avoiding the temptation to speak at the people across from them.

“When we sign people up, we say, how would you explain this difficult thing to a 9-year-old child or my 80-year-old parent? You have to think really hard. And some people take two or three or four goes to get to that, and we help them. But when they do, you can see that a penny has dropped for them. They think, ‘Okay, actually if we strip it right back, this is not a headline, but it's just a very accessible way of describing it. And it's not dumbing down in any sense. It's a way of opening up.’”

Once open, this becomes a conversation where the listening and the learning go in both directions. As Galloway explains, “Stepping into The Hopes and Fears Lab asks for real vulnerability from our scientists – it’s about saying ‘this is what I feel,’ rather than ‘this is what I know,’ which is not at all what they are commonly trained to do!”

Then the day came when the rubber hit the road, and not just for the buses. Would people respond to the environment the team had curated? Would they sit down with scientist and ask questions? Would the participating scientists engage and enjoy themselves?

“The first time we did it, I couldn't believe it. Within 15 minutes, all nine of our scientists were absolutely beaming,” said Galloway. “We had scientists who had only signed up for the first day asking if they could come back the second day.”

And it wasn’t just that it was rewarding and enjoyable for the researchers who participated. It made them think differently about their work in some cases.

“They've always been impressed with the quality of the questions they've got,” said Galloway. “The very first one we did, somebody in cancer research came up to me and said, ‘I've just been asked the best question I've ever been asked.’”

That researcher was asked by a young participant, “Why are you spending all this time trying to cure cancer? Why don’t you just stop cancer from happening in the first place?” The scientist told Galloway, “That really made me think.”

For another participating AI scientist on the bus project, the thrill of speaking with the public was so gratifying that she told Galloway she was going home to research science engagement careers.

Equally as rewarding for Galloway was seeing members of the public, whether eager or shy, benefiting from the interaction with scientists they are unlikely to speak to otherwise. She recalls a bicycling food delivery person stopping by to read information panels on the outside of the buses but turning down an invitation to go inside and participate. After a few more minutes of reading, though, he asked if he could go inside just to listen. Galloway offered to watch over his bike, so he could step on the bus to observe. “The next time I looked over, about 15 minutes later, he was sitting down and talking, and I was just silently punching the air,” laughed Galloway.

After several successful Hopes and Fears Labs, the Kavli Centre team wants to share what they’ve learned with others who want to replicate it in their communities and run their own Hopes and Fears Lab. For what they’re calling “Hopes and Fears in a Suitcase,” the team is creating a “mini manifesto” which will offer guidance on using artwork and cardboard to create the space, how to brief the participating scientists, what makes a good question, and how to manage the room and make it feel welcoming.

For Galloway, it’s important to use well-researched, creative, and thoughtful methods to engage different publics in science and have authentic dialogue, and not rely on traditional outreach like lectures and panel discussions.

“In panels, and with what I call the ‘roving microphone of death,’ you get about four questions and everyone else goes home frustrated because they haven't had a chance for anything real. But we’ve proved we can do things differently in just 15 minutes, which is extraordinary.”