Babies Process Language in a Grown-Up Way

(Originally published by the University of California, San Diego)

January 25, 2011

Babies, even those too young to talk, can understand many of the words that adults are saying – and their brains process them in a grown-up way.

Combining the cutting-edge technologies of MRI and MEG, scientists at the University of California, San Diego show that babies just over a year old process words they hear with the same brain structures as adults, and in the same amount of time. Moreover, the researchers found that babies were not merely processing the words as sounds, but were capable of grasping their meaning.

This study was jointly led by Eric Halgren, PhD, professor of radiology in the School of Medicine, Jeff Elman, PhD, co-director of the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind at UCSD, and first author, Katherine E. Travis, of the Department of Neurosciences and the Multimodal Imaging Laboratory, all at UC San Diego. The work is published this week in the Oxford University Press journal Cerebral Cortex. All authors are members of the Kavli Institute for Brain & Mind.

“Babies are using the same brain mechanisms as adults to access the meaning of words from what is thought to be a mental 'database' of meanings, a database which is continually being updated right into adulthood,” said Travis.

Previously, many people thought infants might use an entirely different mechanism for learning words, and that learning began primitively and evolved into the process used by adults. Determining the areas of the brain responsible for learning language, however, has been hampered by a lack of evidence showing where language is processed in the developing brain.

While lesions in two areas called Broca’s and Wernicke’s (frontotemporal) areas have long been known to be associated with loss of language skills in adults, such lesions in early childhood have little impact on language development. To explain this discordance, some have proposed that the right hemisphere and inferior frontal regions are initially critical for language, and that classical language areas of adulthood become dominant only with increasing linguistic experience. Alternatively, other theories have suggested that the plasticity of an infant’s brain allows other regions to take over language-learning tasks if left frontotemporal regions are damaged at an early age.

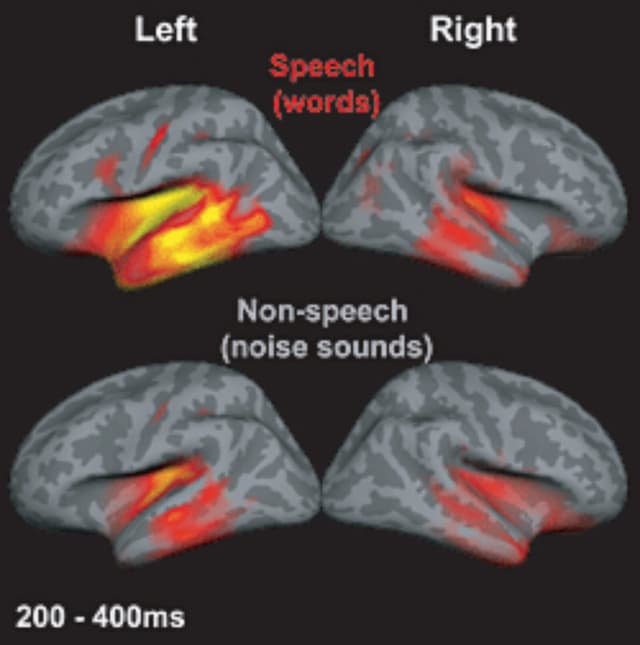

In addition to studying effects of brain deficits, language systems can be determined by identifying activation of different cortical areas in response to stimuli. In order to determine if infants use the same functional networks as adults to process word meaning, the researchers used MEG – an imaging process that measures tiny magnetic fields emitted by neurons in the brain – and MRI to noninvasively estimate brain activity in 12 to 18-month old infants.

In the first experiment, the infants listened to words accompanied by sounds with similar acoustic properties, but no meaning, in order to determine if they were capable of distinguishing between the two. In the second phase, the researchers tested whether the babies were capable of understanding the meaning of these words. For this experiment, babies saw pictures of familiar objects and then heard words that were either matched or mismatched to the name of the object: a picture of a ball followed by the spoken word ball, versus a picture of a ball followed by the spoken word dog.

Brain activity indicated that the infants were capable of detecting the mismatch between a word and a picture, as shown by the amplitude of brain activity. The “mismatched,” or incongruous, words evoked a characteristic brain response located in the same left frontotemporal areas known to process word meaning in the adult brain. The tests were repeated in adults to confirm that the same incongruous picture/word combinations presented to babies would evoke larger responses in left frontotemporal areas.

“Our study shows that the neural machinery used by adults to understand words is already functional when words are first being learned,” said Halgren, “This basic process seems to embody the process whereby words are understood, as well as the context for learning new words.” The researchers say their results have implications for future studies, for example development of diagnostic tests based on brain imaging which could indicate whether a baby has healthy word understanding even before speaking, enabling early screening for language disabilities or autism.

Additional contributors include Matthew K. Leonard, Timothy T. Brown, Donald J. Hagler, Jr., Megan Curran, and Anders M. Dale, all of UC San Diego School of Medicine and KIBM. The research was begun with a seed grant from the KIBM, and funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.