The Year in Brains

A look back at the newsmaking neuroscience of 2019

Looking back at the year in neuroscience leaves one awed at the progress scientists are making in understanding the brain and humbled by the enormity of the task. This roundup starts with two neuroscientists whose work made international headlines this year. One questioned the dogma that brain death is final and irreversible; the other rethought the process of decoding speech signals in order to develop better prostheses. And we end with an example of how transformative interdisciplinary research can be, including the enormous contributions of neuroscientist Bruce McEwen of The Rockefeller University who helped the world understand the health consequences of chronic stress.

- Scientific Headliner

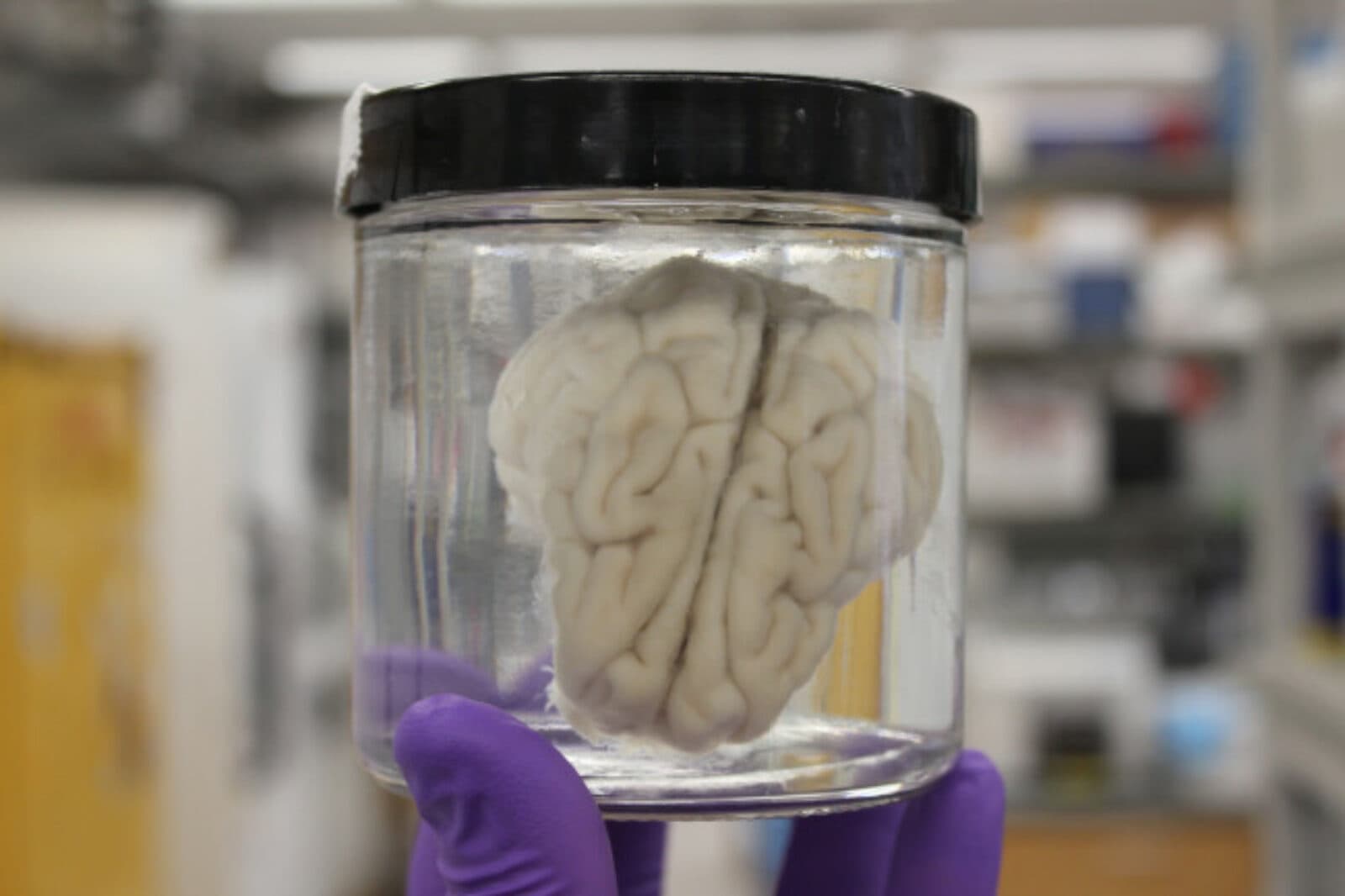

Nenad Sestan, a neuroscientist at the Kavli Institute for Neuroscience at Yale University, was named one of 10 people who mattered in science in 2019 by the journal Nature for research that challenged definitions of life and death. Back in July, we predicted he might have performed the neuroscience experiment of the year, if not the decade, when he revived circulation and some cellular activity in disembodied pigs’ brains. The research was catalyzed by his research team’s observations in postmortem brain tissue that some cells remained viable for hours after death. Sestan’s research also made Discover magazine’s year-end list of the top science stories of 2019, coming in at #13.

- New Translation

Discover also named neurosurgeon Edward Chang, from the Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience at UC San Fransisco, to its annual list (#38) of top science stories. In “Meet the Neuroscientist Translating Brain Activity into Speech,” Chang describes how his team used artificial intelligence to decode patterns of activity in the brain’s speaking center and translate those patterns into speech—with approximately 70 percent accuracy. The technology even managed to maintain the speaker’s intonation. Chang’s goal is to restore speech in people with brain injuries such as stroke and neurological disorders like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Stress Spectrum

Not everyone responds to stress the same way: It can drive some people into depression whereas demonstrate resilience. But can those differences be predicted? Researchers in Bruce McEwen’s lab, at the Kavli Neural Systems Institute at The Rockefeller University, which studies the impact of stress on the brain, set out to answer that question. Working with mice, which also exhibit a spectrum of responses when faced with stress, they identified a set of biological factors, or biomarkers, that can be used to predict how an animal will respond to stress. The research raises the possibility that a similar test could be developed for humans.

- Remembering Bruce McEwen

Bruce McEwen, whose pioneering research on how stress hormones, such as cortisol, influence brain structure and function, died January 3, following a brief illness. In a statement published by Rockefeller, Leslie Vosshall, director of the Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience, remembered McEwen: “Bruce was a giant in the field of neuroendocrinology,” she said. “He was a world leader in studying the impact of stress hormones on the brain, and led by example to show that great scientists can also be humble, gentle, and generous human beings.”

To learn more about McEwen and his boundary-crossing research, read this fascinating interview from last November, published in Rockefeller’s Seek magazine, in which McEwen discussed how—and why—his research was moving beyond questions of biology to sociopolitical ones.